We can contribute to science even in death, through cadaver donation. This piece is a tribute to all the honorable individuals who chose to donate their bodies for the advancement of medical science.

We live our lives, things happens and eventually the day comes - for everyone.

When I hear the phrase The dead teach the living, I immediately think of our anatomy dissection hall. All the days we spent with cadavers looking at internal structures of human body, how to navigate through all the muscles while carefully preserving the nerves and blood vessels.

When I mention Dead teach Alive, it encompasses every lesson a medical student learns from a cadaver—from spatial orientation to surgical discipline. Likewise, Dead save Alive includes all the applications of those lessons learnt from dissections that ultimately go towards treating for the benefit of the patients.

Planning

In our college, we are divided into groups of 20 per strecher. Each day, four members get to dissect. Remembering how we learn through cadaveric dissection and me staying up late to briefly review anatomy - usually only the night before my turn. It was difficult pointing out structures even with prior preparation. Eventually things got easier though.

Planning isn’t my forte, but I soon learned that it’s a prerequisite for dissection. I eventually realised, if I didn’t plan on how to perform the dissection, where the incisions are supposed to go and learn briefly about anatomical positions and relative positions of other parts, I will have to stand there with a blank face and nod my head as our professors dissect the cadaver and show us how its done. That was passive learning, and I wanted more. As soon as I realised prior preparation is the key to active engagement, final exams were upon us.

Bottom line is that to practice active learning, minimise errors and improve efficiency of a task, the better you plan, the fewer things go wrong - though planning doesn’t guarantee everything will go right.

Tactile Feedback

I still remember how confidently I cut through the deltoid muscle only to discover I cut through a blood vessel underneath it. I was terrified to see that blood vessel cut.

Why? Beause the next thing that hit me was, What if I cut a vein or artery by mistake, like this, in a patient undergoing surgery and they bleed to death? I was naive. The twist is structures so clearly visible in a cadaver dissection don’t look so similar(not even close) or clear in a real surgical setting. Everything looks red. It becomes a challenge to navigate the surgical site anatomy sometimes. Hence, surgical procedures demand the highest level of precision and expertise(built through experience) to minimize risks and maximize benefits for the patient.

This incident taught me how careful I need to be when cutting through a tissue(even if its a cadaver or a patient undergoing surgery). Your concentration should be at your max level, and you should be able to feel everything that touches your scalpel(the tactile/ haptic feedback, a sensitivity even the most advanced robotic surgical systems have yet to replicate) to make precise and accurate cuts. Tactile feedback is a safety layer protecting you from making mistakes. Yet, tactile feedback alone isn't a reliable safeguard - it’s a supplementary skill that helps minimize the risk of error.

Legacy

In resource-limited settings, mannequins often serve as substitutes for cadavers. These simulation tools not only aid in learning anatomy but also provide hands-on training in essential clinical skills such as injection administration, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and airway management. Importantly, it is through working with the inanimate - whether cadavers or mannequins - that learners are granted a safe environment to make mistakes, reflect, and refine their techniques, ultimately ensuring better performance and reduced error in real-world patient care.

When I look back, those cold, silent bodies were more than teaching tools - they were silent mentors. They taught us not just anatomy, but humility, patience, and respect. They absorbed our errors without consequence, allowing us to grow through imperfection. Each cut, each hesitation, each realization shaped not just my hands but my mind. As we move closer to the clinical world, where real lives are at stake and second chances are rare, I carry those lessons with me. In a way, every diagnosis I make, every procedure I perform, and every patient I help will bear a trace of what I first learned in that dissection hall.

The dead teach the living. The dead save the living. And in their silence, they speak volumes.

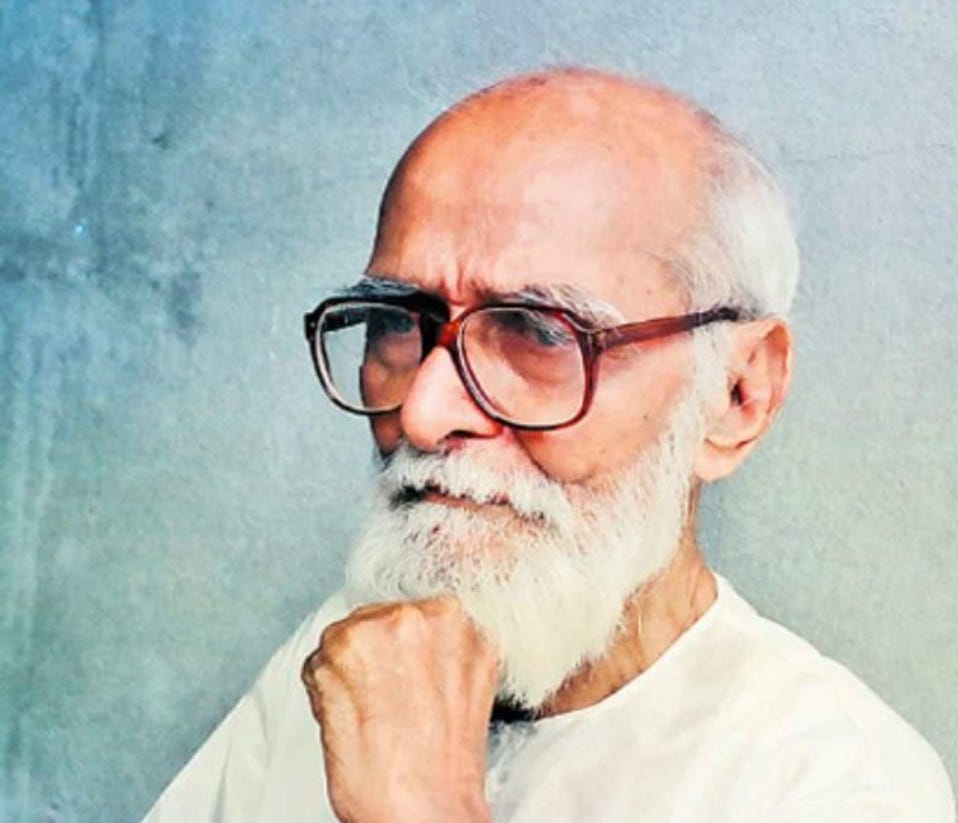

With deep respect to Shri Kaloji Narayana Rao garu, whose legacy and courageous decision to donate his body continues to inspire and advance the cause of medical science and education.

0 Comments